With their versatile applications, gas sensing technologies have transformed care in clinical settings for decades.

One key example is capnography, which measures the carbon dioxide (CO2) exhaled by patients during anaesthesia and in intensive care settings, in which precise CO2 monitoring is crucial to prevent hypoventilation and ensure patient stability.

Gas sensors, particularly those working in the mid-infrared (MIR) range, are now being used for a wider range of applications, including the management of indoor air quality in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and other public spaces.

Simultaneously, advances in gas analysis are unearthing new diagnostic pathways, with exhaled breath demonstrating potential as a non-invasive biomarker for conditions such as sleep apnoea, metabolic disorders, and diabetes.2,3

This article explores how innovations in gas sensing are transforming public health, from monitoring air quality in shared spaces to enabling new clinical and diagnostic applications.

The Importance of Monitoring Air Quality in Public Spaces

Exposure to CO2 and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) can lead to negative health effects such as fatigue, cognitive impairment, and respiratory complications. Gas sensing is, therefore, an essential component of real-time air quality surveillance in communal and public environments.1

The continued monitoring of CO2, VOCs, and other pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and fine particulates (PM2.5) provides crucial data for the management of urban health risks. This is the case particularly for vulnerable people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, or cardiovascular conditions.4

These technologies are also central to crisis prevention, helping to detect flammable or toxic gases that can amass undetected in enclosed spaces such as tunnels, underground transport systems, or crowded public venues. Using sensitive, rapid-response gas sensors in such settings ensures that dangerous conditions are identified as early as possible, thus lowering the chance of medical emergencies or mass exposure events.

This presents a unique challenge, since hospitals and city centers are both complicated environments, within which a variety of gases are concurrently present, and cross-interference can make selective detection more tricky.

The necessity for reliability and speed is especially vital in medical settings, with clinicians relying on near-instant readings to make treatment decisions for different patients. Similarly, public monitoring systems need continued, drift-free operation to supply trustworthy data over extended periods with no need for recurring recalibration.

Choosing the Right Gas Sensing Solution

It is crucial that the best gas sensing equipment is chosen for each unique application and setting. Gas sensing systems operate in different parts of the infrared (IR) spectrum, and the chosen range has a direct impact on the system’s performance.

Near-infrared (NIR) detectors are well developed following decades of work in the telecommunications industry, and they usually have a high sensitivity, but their overlapping absorption signals make the distinction between different gases in complex mixtures challenging.

Contrastingly, many gases have their strongest and most distinct absorption fingerprints in the MIR range, making it easier to separate signals, reducing cross-interference.5 This high level of selectivity is fundamental in the complex environments that are hospitals and urban centers.

Historically, lead and mercury devices were used for such applications. Now, indium arsenide antimonide (InAsSb) detectors offer a safer, quicker, and more reliable RoHS-compliant alternative, supplying high performance without compromising on sensitivity. These detectors can be combined with MIR LEDs to develop compact, energy-efficient systems that are well-suited for the continuous monitoring of CO2 and NO2 in hospitals and other public areas.

As some of the most advanced options, quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) are MIR sources that simultaneously deliver both extremely high specificity and sensitivity. They are capable of resolving multiple trace gases in exhaled breath, and can be used in emerging glucose monitoring applications, and the detection of complex pollutant mixtures in urban air.6

Acknowledging Current Adoption and Implementation Challenges

The uptake of sophisticated gas sensing technologies in public health has been slow despite their potential, with the majority of hospitals and municipalities continuing to use legacy systems: higher-end options such as QCLs are not yet widely used.

Often, these organizations rely on traditional systems like filament lamps or lead-salt detectors, simply because they are well-known and supported by existing infrastructure. In some cases, regulatory limitations and exemptions have hindered the change to safer and more accurate alternatives.5

The majority of medical and public health devices also remain focused on using single gases, even though multi-gas sensing could provide a much superior understanding of patient health and environmental exposure.

For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, CO2 monitors were quickly deployed in schools and workplaces to track ventilation quality, but such devices generally only measured a single parameter, leaving other crucial indoor pollutants undetected.7

Integration also presents barriers, since new detector technologies often require robust data management systems, congruous electronics, and staff training to be effectively implemented, providing a challenge for already resource-constrained healthcare providers.

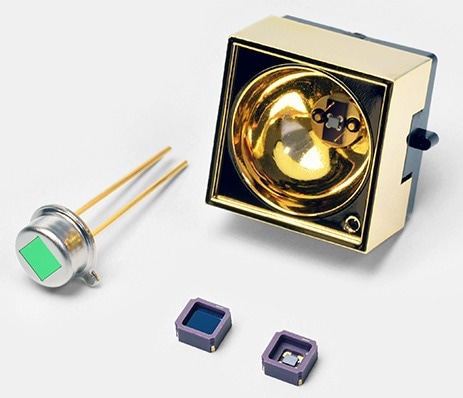

Mid-infrared LEDs L1589X series. Image Credit: Hamamatsu Photonics Europe

Developing Smarter Sensors for Healthier Communities

The future of gas sensing in the public health sector lies in smarter and better-connected systems capable of generating actionable data at scale. In urban environments, networks of distributed sensors have the potential to track pollution hotspots in real time, allowing authorities to respond efficiently and protect endangered populations from dangerous exposure.

In healthcare, the development of wearable gas sensors could have a significant impact on disease management by enabling the continuous monitoring of chronic conditions, providing clinicians with real-time data on their patients.

These innovations are also being driven by tightening policy frameworks, as both the EU and the WHO are establishing increasingly stringent air quality standards, with gas sensing technologies playing a crucial role in adhering to these requirements. The aforementioned growing use of CO2 monitoring in workplaces and schools during and after the COVID-19 pandemic is a key example, with measurements increasingly linked to cognitive performance, infection control, and student concentration.8

Progress Depends on Partnership

Close collaboration between public authorities, technology providers, and healthcare systems is crucial to deliver healthier environments.

Gas sensing is about more than individual components: it is also important to integrate these detectors and sources into systems that deliver reliable data where it matters most, including hospital wards and urban air monitoring networks.

Hamamatsu supports this effort with a broad portfolio of NIR and MIR solutions designed for real-world performance, developing detectors and light sources that combine stability, high sensitivity, and compliance with modern safety standards. The company collaborates with partners across healthcare and environmental monitoring to develop viable tools that support public health.

To learn more about this topic, you can watch an on-demand panel discussion where industry experts dive into the latest advances in MIR technologies and talk about what they mean for gas sensing.

References

- Snow, S., et al. (2019). Exploring the physiological, neurophysiological and cognitive performance effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentrations indoors. Building and Environment, 156, pp.243–252. DOI: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.04.010. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360132319302422.

- Nowak, N., et al. (2021). Validation of breath biomarkers for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Medicine, 85, pp.75–86. DOI: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.040. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1389945721003750.

- Dixit, K., et al. (2021). Exhaled Breath Analysis for Diabetes Diagnosis and Monitoring: Relevance, Challenges and Possibilities. Biosensors, 11(12), p.476. DOI: 10.3390/bios11120476. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6374/11/12/476.

- Wan Mahiyuddin, W.R., et al. (2023). Cardiovascular and Respiratory Health Effects of Fine Particulate Matters (PM2.5): A Review on Time Series Studies. Atmosphere, (online) 14(5), p.856. DOI: 10.3390/atmos14050856. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4433/14/5/856.

- Hamamatsu Photonics. (2015). Beyond Gas Sensing Panel Discussion | Hamamatsu Photonics. (online) Available at: https://www.hamamatsu.com/eu/en/resources/webinars/infrared-products/beyond-gas-sensing-panel-discussion.html.

- Wörle, K., et al. (2013). Breath Analysis with Broadly Tunable Quantum Cascade Lasers. Analytical Chemistry, 85(5), pp.2697–2702. DOI: 10.1021/ac3030703. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ac3030703.

- University of Cambridge. (2022). Curbing COVID-19 in schools: Cambridge scientists support CO2 monitor rollout. (online) Available at: https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/curbing-covid-19-in-schools-cambridge-scientists-support-co2-monitor-rollout.

- Dedesko, S., et al. (2025). Associations between indoor air exposures and cognitive test scores among university students in classrooms with increased ventilation rates for COVID-19 risk management. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. (online) DOI: 10.1038/s41370-025-00770-6. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41370-025-00770-6.

This information has been sourced, reviewed, and adapted from materials provided by Hamamatsu Photonics Europe.

For more information on this source, please visit Hamamatsu Photonics Europe.