Image Credit: NASA/Benjamin Hockman

A New Approach to an Old Challenge

Until now, studying the inside of small bodies has meant working with surface data from orbiters and landers. These missions provide useful information, but their spatial resolution is limited, especially when it comes to spotting variations deep below, like hidden voids or dense rock formations.

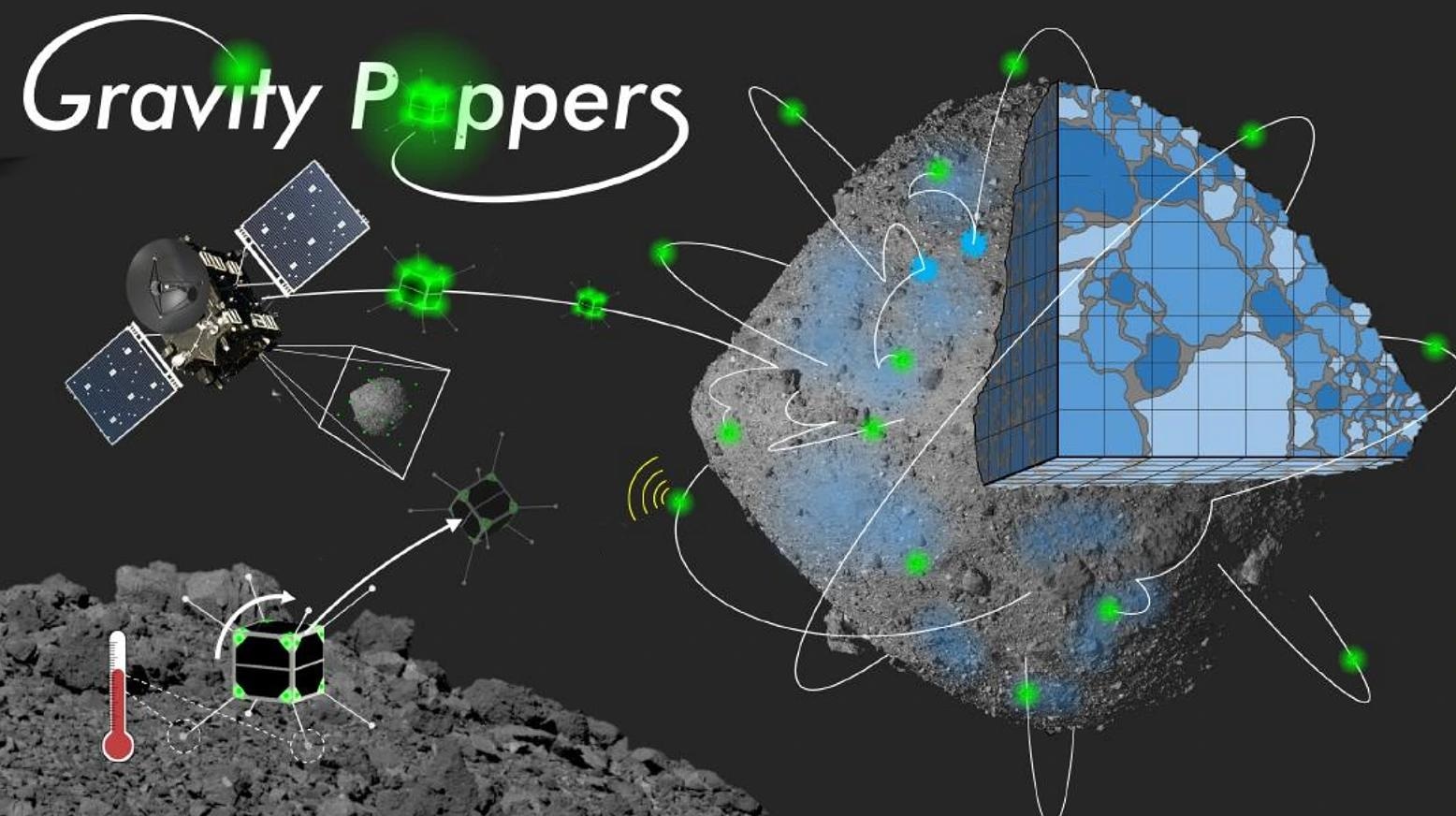

The Gravity Poppers concept takes a different path. Instead of relying on a single platform, it sends out a swarm of compact, mobile probes. Each one is built to survive an environment where gravity is almost nonexistent and the landscape is rough, uneven, and littered with debris. These probes don’t roll or crawl - they hop.

With each leap, they touch down on a new spot, sampling the local gravity field as they go. The idea is to gather hundreds or thousands of data points across a surface that’s often chaotic and unpredictable. Above, a spacecraft tracks the bouncing swarm, capturing their trajectories with high precision using radio or optical signals.

How it Works

Each Gravity Popper is a small, rugged device - just big enough to carry essential sensors and tracking hardware. Designed for simplicity and durability, the probes are fitted with instruments to read surface temperature and mechanical strength. The hopping mechanism gives them mobility without the need for wheels or complex propulsion systems.

Their motion isn’t random. It’s a controlled pattern of bouncing, designed to maximize coverage and generate a diverse set of gravity readings. As the probes move, their paths are recorded from orbit. The data is then fed into algorithms that use those trajectories to refine models of the asteroid’s internal mass distribution.

The process works iteratively. With each hop, the system gains more clarity, gradually building a high-resolution gravity field map that reveals features hidden below the surface. It’s a method that combines mechanical design, real-time tracking, and advanced computation into a lightweight, modular package.

What the Early Tests Show

Initial assessments, both simulated and physical, indicate that the system works. In tests, the hopping probes were able to detect slight variations in the gravity field that pointed to underlying structures like boulders or hollow spaces. That level of precision marks a meaningful step beyond what existing methods can offer.

One key insight highlighted that the probes can localize dense features just beneath the surface by reading the tiny gravitational tugs they exert. Over time, and with enough coverage, this capability could provide a remarkably clear picture of what an asteroid is made of - layer by layer.

The team also explored trade-offs. Miniaturization must be balanced against durability. Tracking needs to remain accurate even as probes scatter unpredictably. Algorithms must process large volumes of complex data in near real time. The concept shows promise, but success depends on getting these details right.

The Road Ahead

Challenges remain. The hopping mechanism needs to last through repeated impacts. The tracking system must stay reliable even in rough conditions. And the software must scale to handle larger, more complex missions. But the foundation is solid, and early prototypes have shown strong results.

The Gravity Poppers project opens a new way of interacting with small bodies - not just watching them from afar, but engaging with them in a physical, distributed, data-rich way. With every hop, the probes peel back another layer, building toward a complete picture of the body’s interior.

If further development goes well, these tiny machines could play a big role in how we study and work with asteroids in the years ahead. Whether it's for science, safety, or future exploration, the ability to see inside these rocky remnants of the early Solar System could make all the difference.