As healthcare systems continue shifting toward personalized and point-of-care (POC) models, SPR biosensors are increasingly being explored for monitoring biomarkers, identifying pathogens, and supporting clinical decision-making.

Early diagnosis plays a decisive role in managing many chronic diseases, particularly those that remain asymptomatic for extended periods before progressing to serious conditions such as cervical cancer or liver disease.

Traditional diagnostic techniques, while reliable, frequently require specialized infrastructure, trained personnel, and significant processing time. These constraints can limit access, especially in decentralized or resource-limited settings.

Biosensors help bridge this gap by enabling earlier and more accessible detection across medical, environmental, and research fields.

Electrochemical and mass-based biosensors are already well established, but plasmonic biosensors offer a different set of strengths.

Real-time monitoring, label-free operation, rapid response, high sensitivity, and the possibility of reuse make SPR-based systems especially appealing for diagnostic applications, including POC testing .1,2

Get all the details: Grab your PDF here!

An Overview of SPR Biosensors

SPR is an optical sensing technique that detects target molecules by tracking changes in the refractive index near a metal sensor surface. When biomolecules bind to the surface, they modify the local dielectric environment, which in turn shifts the resonance condition of surface plasmons.

Because these shifts are highly sensitive to surface-level changes, SPR can detect even subtle biomolecular interactions.

Exciting surface plasmons requires an optical coupling mechanism. Early SPR systems relied on prism-based attenuated total reflection (ATR) configurations, most notably the Kretschmann setup.

Over time, the technology has expanded to include optical fiber-, waveguide-, and grating-based configurations, offering greater flexibility in sensor design and deployment.

At the core of SPR are surface plasmons or surface plasmon polaritons, which arise from collective oscillations of free electrons at the interface between a metal and a dielectric medium.

This phenomenon enables label-free and non-invasive monitoring of biomolecular binding events. While SPR biosensors operate on the same fundamental principle, they differ in the plasmonic modes they use and in how those modes are excited and measured.1,2

Two plasmonic modes dominate biosensing applications: localized surface plasmons (LSPs), typically supported by metal nanoparticles, and propagating surface plasmons (PSPs), supported by continuous metal films. Sensors based on either or both modes fall under the broader category of SPR biosensors.

More recent designs incorporate additional plasmonic effects, such as nanohole array resonances, Fano-like resonances in nanoparticle clusters, coupling between localized and propagating plasmons, surface lattice resonances, and waveguiding modes in patterned metallic structures.

These modes differ in how electromagnetic fields are distributed and in the extent to which they extend from the sensor surface.

Penetration depths can range from just a few nanometers for localized modes to hundreds of nanometers or more for long-range modes. This variability allows SPR biosensors to be tuned for specific targets and sample types.

A key advantage is the ability to monitor binding kinetics and affinity in real time, without labels that can interfere with natural biomolecular interactions.

With detection sensitivities reaching pg/μL levels, quantitative outputs, strong miniaturization potential, and compatibility with SPR imaging, the platform continues to evolve as a flexible and effective biosensing approach.1,2

Developments in Optical Platforms

Traditionally, SPR biosensors have relied heavily on thin-film attenuated total reflection (ATR) configurations. While these systems remain widely used, their sensitivity is now largely limited by physical noise.

However, recent advances increasingly combine ATR with nanostructures and nanoparticles to exploit diverse plasmonic modes.

Plasmonic microscopy has become an important extension of SPR, enabling localized measurements, digital detection strategies, and even single-particle analysis.1

These capabilities reduce reagent consumption and overall assay costs while offering more detailed analytical insight.

In parallel, efforts to simplify optical layouts, such as free-space collinear excitation, are helping to reduce system complexity and cost, making SPR more suitable for portable and POC devices.

Another major driver of progress is the integration of SPR components with microfluidic systems. These optofluidic platforms improve sample handling, reduce assay times, and support automated operation, all of which are important for clinical adoption.1

Developments in Detection Formats

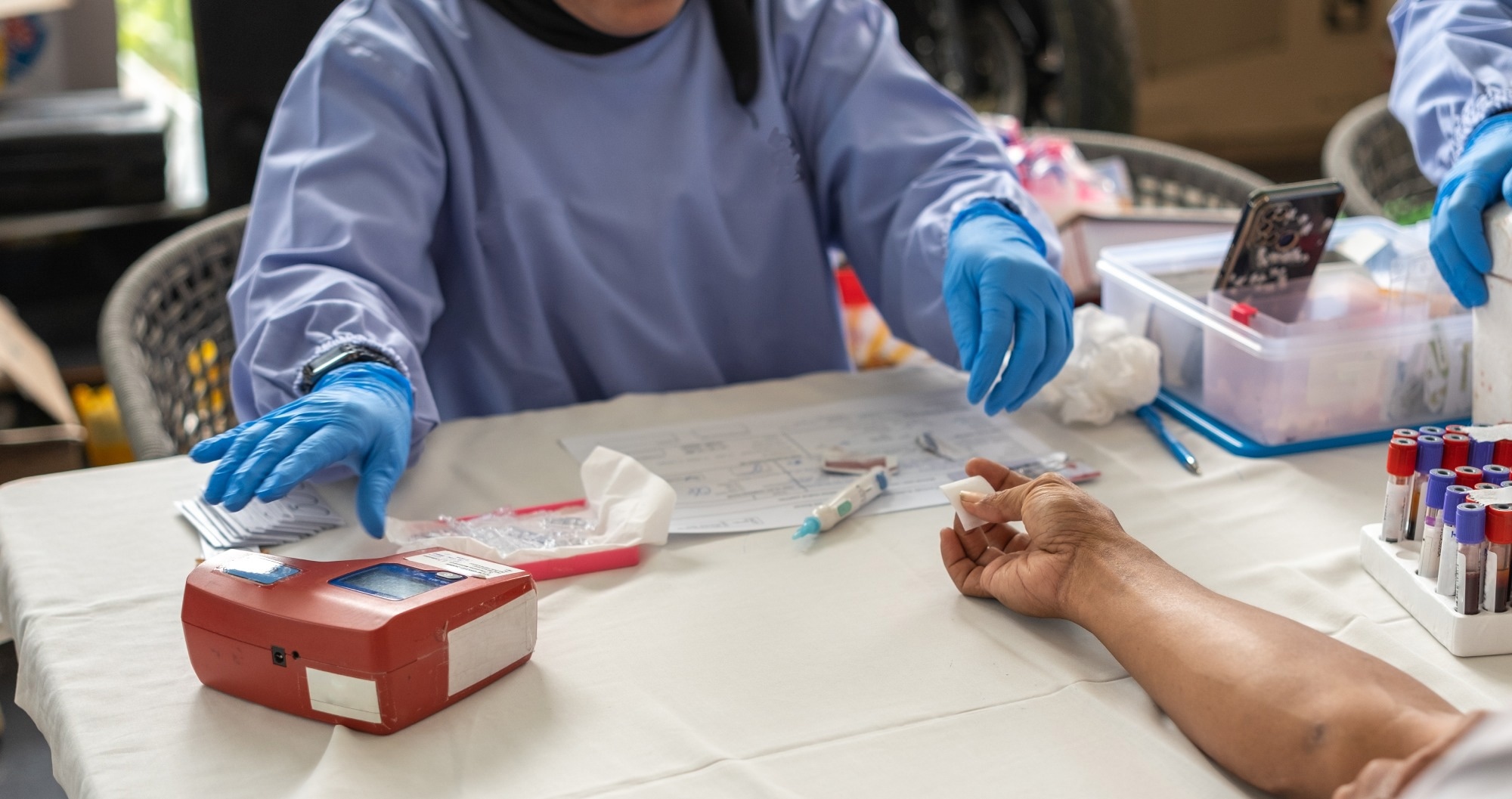

Image Credit: InveStock/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: InveStock/Shutterstock.com

Working with real clinical samples presents clear challenges.

Biological fluids contain many components that can bind nonspecifically to sensor surfaces, and target analytes are often present at concentrations far below those of background molecules.

Together, these factors can compromise sensitivity and specificity.

To address this, a range of detection formats have been developed to boost specific signals while minimizing nonspecific responses. The sandwich assay is one of the most common approaches.

In this format, functionalized metal nanoparticles (gold nanospheres or nanorods, silver nanocubes, or receptor-coated liposomes) are used to amplify the SPR signal.

Because these particles are introduced in controlled buffer solutions, they enhance specific binding events much more than nonspecific interactions.

Several refinements of sandwich assays have recently been reported. In one example, a report demonstrated a dual-enzyme-assisted sandwich assay for detecting the protein secretogranin II (SCG2).

After forming a multilayer sandwich complex on the sensor surface, a tyramide reaction biotinylated neighboring proteins, allowing streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase to generate an insoluble precipitate whose deposition further amplified the signal.

This method achieved a detection limit of 16 pg/mL in 10 % blood serum.1

Other strategies focus on selectively removing nonspecific signals. A nanoparticle-release assay for nucleic acid detection used surface-bound oligonucleotide probes to capture microRNA targets and bind gold nanoparticles. A displacing DNA strand then released only specifically bound nanoparticles, improving signal accuracy and enabling sub-fM detection in 10 % plasma.1

Enzyme-assisted detection formats have expanded capabilities. One study combined a DNA-walking mechanism with nuclease-mediated cleavage to quantify microRNA-182. Cycles of hybridization and cleavage progressively reduced biotin density on the sensor surface, producing an inversely proportional signal over a linear range of five to 1000 fM. The assay successfully detected microRNA-182 in 20 % serum.

Beyond molecular targets, SPR is now being applied to structural biomarkers. In one study, misfolded proteins in plasma were captured using heat shock protein 70-functionalized surfaces and released under controlled nucleotide conditions.

The proteins were then identified using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Elevated levels of misfolded proteins were observed in specific stages of myelodysplastic syndrome, highlighting the diagnostic relevance of this approach.1

Biomarker Detection

SPR biosensors have been applied to a wide range of targets, including nucleic acids, proteins, viruses, bacteria, and even whole cells. A commercial SPR system (BioNavis), for example, detected cancer stem cells from acute myeloid leukemia patients by using antibodies against CD133.

Clear differences were observed between patient samples and healthy controls at concentrations of 1 × 105 cells/mL.

SPR imaging has also been used for bacterial serotyping. One prism-based system detected Escherichia coli O-antigens with limits of detection between 1.1 to 17.6 × 106 CFU/mL and correctly identified nearly all clinical isolates tested.1

In viral detection, an LSPR biosensor identified the CoV NL63 coronavirus using human angiotensin-converting enzyme two immobilized on silver nanotriangles, with detection limits around 103-104 PFU/mL in saliva.

In oncology, HER2-positive exosomes from breast cancer cells were detected using an aptamer-based SPR sensor with nanoparticle-assisted amplification, achieving limits of 104 exosomes/mL.

Commercial platforms such as Navi™ 220A NAALI and Biacore™ systems have also been used to detect dengue virus, troponin T, and cancer-related proteins using sandwich and aptamer-based assays.

Collectively, these examples demonstrate the versatility of SPR biosensors across a wide range of diagnostic targets.1

Recent Developments

Recent studies continue to refine SPR sensor performance. One report in Plasmonics proposed a SPR sensor configuration combining a BK-7 prism, barium titanate layer, and a gold layer, which demonstrated exceptional performance in detecting cancer-associated biomolecular targets.

By optimizing layer thickness and recognition elements, the sensor showed clear resonance angle shifts corresponding to biomarker concentration, indicating strong sensitivity and stability in complex samples.3

Another study in Optics and Lasers in Engineering examined a multilayer SPR biosensor based on fanckeite and transition metal dichalcogenides on silver for Pseudomonas detection.

The optimized structure achieved a maximum sensitivity of 212.42 deg/RIU over a refractive index range of 1.33-1.40, demonstrating improved signal quality and detection accuracy.4

Saving this article for later? Grab a PDF here.

Conclusion

SPR biosensors combine real-time, label-free detection with high sensitivity and broad applicability across biomarker types.

Continued advances in optical design, plasmonic structures, and detection strategies are steadily improving performance while supporting more compact and cost-effective systems.

As these developments continue, SPR biosensors are well-positioned to support earlier diagnosis, personalized medicine, and point-of-care testing across a wide range of healthcare settings.

References and Further Reading

- Špringer, T., Bockova, M., Slabý, J., Sohrabi, F., Capková, M., & Homola, J. (2025). Surface plasmon resonance biosensors and their medical applications. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 117308. DOI: 10.1016/j.bios.2025.117308, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956566325001824

- Janith, G. I. et al. (2023). Advances in surface plasmon resonance biosensors for medical diagnostics: An overview of recent developments and techniques. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis Open, 2, 100019. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpbao.2023.100019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949771X23000191

- KVM, S., Pandey, B. K., Pandey, D. (2025). Design of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors for highly sensitive biomolecular detection in cancer diagnostics. Plasmonics, 20(2), 677-689. DOI: 10.1007/s11468-024-02343-z, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11468-024-02343-z

- Janze, E. J. T., Meshginqalam, B., & Alaei, S. (2024). A highly sensitive surface plasmon resonance biosensor using heterostructure of franckeite and TMDCs for Pseudomonas bacteria detection. Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 181, 108404. DOI: 10.1016/j.optlaseng.2024.108404, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0143816624003828

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.